Healed People Forgive Differently

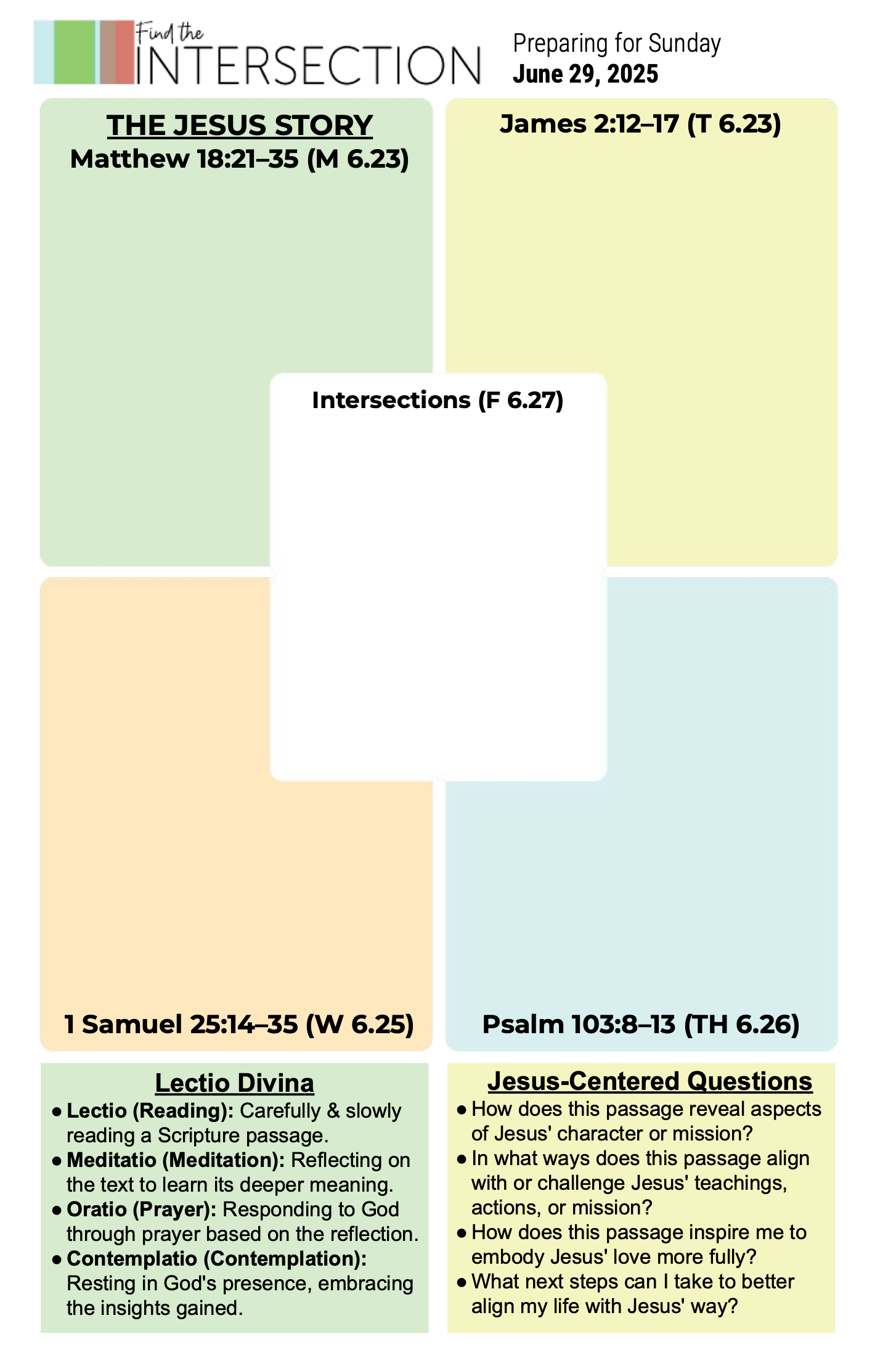

Matthew 18:21–35 | Monday, June 23, 2025

The Gospel According to the Servants – Week 3

How Many Times?

There’s a moment when Peter leans in with a question that has likely crossed all our minds: “How many times should I forgive someone who sins against me?”

Forgiveness is hard. And Jesus doesn’t pretend otherwise.

But instead of giving a reasonable limit, “seven times” sounds generous, Jesus explodes the math with seventy times seven.

This parable is not a soft word.

It is a disruptive story.

It unmasks what mercy really means, how unforgiveness keeps us locked inside the very systems Jesus came to liberate us from.

This is a story about debt, power, and mercy, about the tension between being forgiven and becoming forgiving.

And for those of us seeking to live the Gospel from the bottom-up, as servants and not overlords, it is a confrontation we must take seriously.

Context: Setting the Scene

Literary Context: This parable directly follows Jesus’ teaching on how to handle conflict within the community (Matthew 18:15–20). The topic of forgiveness is central to the entire chapter. Peter’s question becomes a setup for Jesus to redefine forgiveness, not as a one-time act, but a way of being.

Historical Context: Jesus tells this parable in a culture shaped by debt-based economics and imperial rule. The king represents a kind of autocrat who controls the fates of his servants. But Jesus’ use of reversal and irony flips expectations: mercy is offered, then revoked. This is not a story endorsing the king, but exposing how power operates.

Theological Context: Forgiveness, in Jesus’ teaching, is not optional. But more than that, it is meant to reshape how we see justice, debt, and mercy. The parable forces us to wrestle with a central Kingdom truth: we cannot receive mercy without learning how to extend it.

Matthew 18:21–35 (NLT)

21 Then Peter came to him and asked, “Lord, how often should I forgive someone who sins against me? Seven times?”

22 “No, not seven times,” Jesus replied, “but seventy times seven!

23 “Therefore, the Kingdom of Heaven can be compared to a king who decided to bring his accounts up to date with servants who had borrowed money from him.

24 In the process, one of his debtors was brought in who owed him millions of dollars.

25 He couldn’t pay, so his master ordered that he be sold—along with his wife, his children, and everything he owned—to pay the debt.

26 But the man fell down before his master and begged him, ‘Please, be patient with me, and I will pay it all.’

27 Then his master was filled with pity for him, and he released him and forgave his debt.

28 But when the man left the king, he went to a fellow servant who owed him a few thousand dollars. He grabbed him by the throat and demanded instant payment.

29 His fellow servant fell down before him and begged for a little more time. ‘Be patient with me, and I will pay it,’ he pleaded.

30 But his creditor wouldn’t wait. He had the man arrested and put in prison until the debt could be paid in full.

31 When some of the other servants saw this, they were very upset. They went to the king and told him everything that had happened.

32 Then the king called in the man he had forgiven and said, ‘You evil servant! I forgave you that tremendous debt because you pleaded with me.

33 Shouldn’t you have mercy on your fellow servant, just as I had mercy on you?’

34 Then the angry king sent the man to prison to be tortured until he had paid his entire debt.

35 “That’s what my heavenly Father will do to you if you refuse to forgive your brothers and sisters from your heart.”

Key Insights

Mercy is both gift and responsibility. The story doesn’t end with forgiveness, it tests how we respond to being forgiven. Mercy isn’t just received, it must be multiplied.

The king may not represent God. Some scholars, like Ched Myers and William Herzog, argue that the king in this story reflects the oppressive power structures of empire, not the character of God. This view challenges us to see Jesus as critiquing systems where mercy is wielded as control and revoked to preserve dominance.

Unforgiveness perpetuates violence. The man’s refusal to forgive reveals how internalized oppression can turn the oppressed into oppressors. Forgiveness is not weakness, it is a refusal to replicate harm.

Jesus offers a radical alternative to debt culture. In a world obsessed with what people owe us, Jesus calls us to cancel debts, not just financial ones, but emotional and relational ones. To release people is to free ourselves too.

Forgiveness is a communal act. The “other servants” notice the injustice and bring it forward. Forgiveness isn’t just personal, it shapes and disrupts entire communities.

Guiding Question

What debts are you still holding onto—emotional, spiritual, or relational—that Jesus might be inviting you to release?

Yes, forgiveness must be a way of living and seeking the kingdom of God. I still struggle with some relational issues with a few people, honestly. I don't want to and keep choosing forgiveness. Thanks for writing. Have a blessed day.